50 Years Since Shipwreck which Inspired Ballad

- cutlercomms

- Nov 13, 2025

- 6 min read

It is now 50 years since the freighter SS Edmund Fitzgerald sank on Lake Superior on November 10, 1975, with the loss of 29 lives. So what, you might rightfully ask? For there have been greater shipwrecks in peacetime through the years, with far bigger loss of life. True! But few have been immortalized in song like the Edmund Fitzgerald.

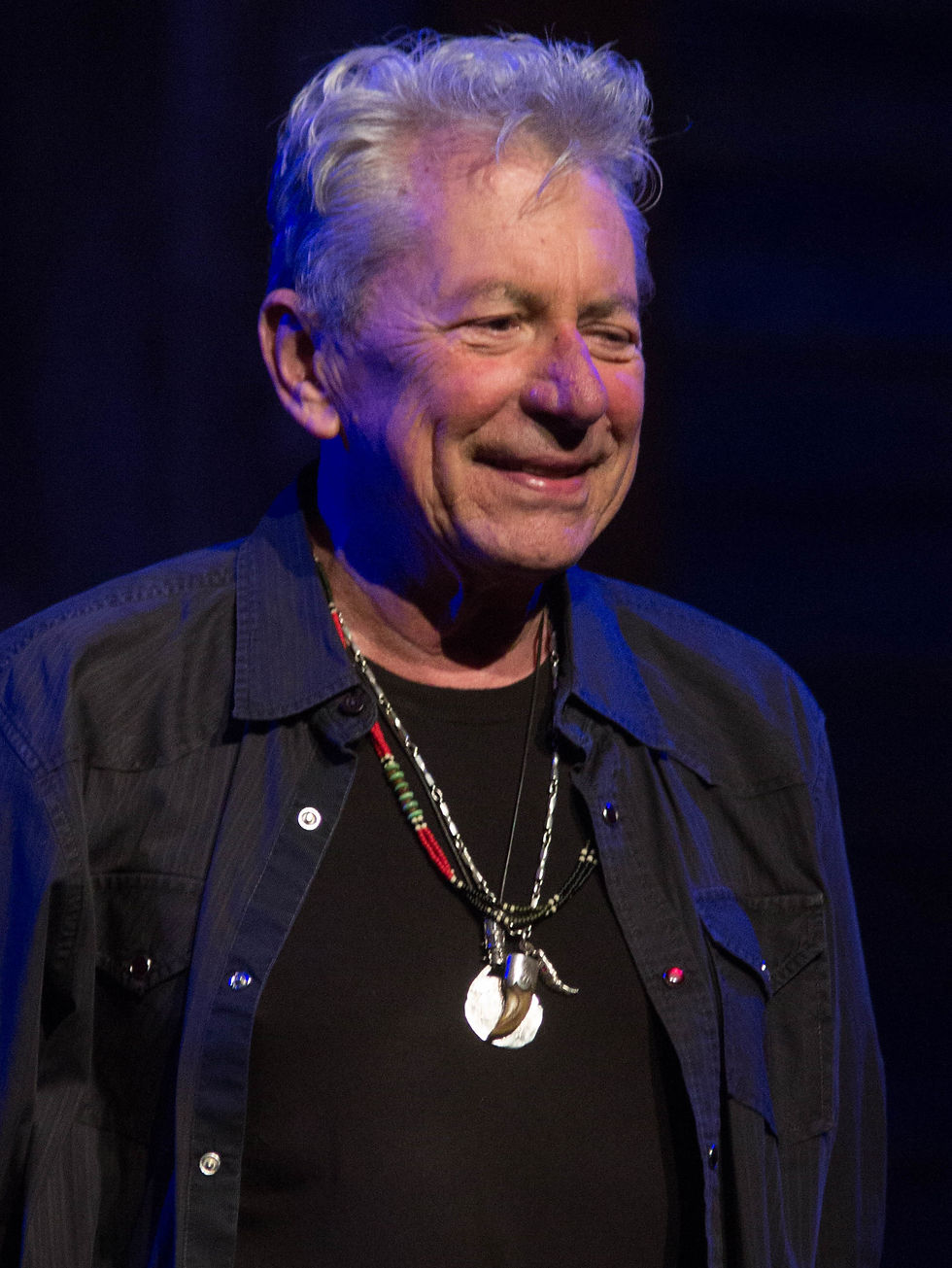

Canadian singer-songwriter Gordon Lightfoot released "The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald" in August 1976. It would be an overnight sensation - topping the Canadian charts and reaching number 2 in the U.S. Billboard Hot 100 - and become regarded as one of the best folk ballads ever written. It would also be nominated for two Grammy Awards.

The impact of his endearing composition was no better reflected than when Lightfoot died in May 2023, fans quipped that "there would be 29 sailors waiting to meet him at heaven's door." And a day after his death, the Mariners' Church in Detroit tolled its bell 30 times - 29 times in memory of the lost crew and the 30th for Lightfoot.

The Edmund Fitzgerald - "Big Fitz" - left the port of Superior, Wisconsin, on November 9, 1975, in fine weather. It was loaded with 26,000 tons of processed iron-ore pellets and bound for an island near Detroit. But the next day, hurricane winds set in, with blinding snow and waves up to 25 feet high. The freighter and its crew of 29 battled the treacherous conditions for several hours before the ship listed and sank near Whitefish Point around 7 p.m. on the 10th. All onboard died and their bodies were never recovered.

As might be expected, the sinking made news across the U.S. and Canada, with Newsweek publishing a story titled “The Cruelest Month.” In fact, it was the Newsweek article – about two weeks after the disaster - which motivated Lightfoot to write about the sinking. He had become aggrieved when he noticed that the magazine had misspelled the boat’s name, calling it “Edmond.” He felt this somewhat dishonoured the dead crew.

Lightfoot wasted no time writing his ballad and it would actually be recorded in Toronto only six weeks after the sinking, though not released for another nine months. Given that during this period, the exact details and cause of the disaster were somewhat sketchy, Lightfoot needed to take artistic license with the lyrics. And this would bother him then and, indeed, for some years to come.

Even by the time he got to the studio, Lightfoot was still fretting over possible inaccuracies until his lead guitarist Terry Clements leaned over and told him: “Just tell the story.” Clements added that this is what his favourite author Mark Twain would say!

There was one stanza in particular, that Lightfoot agonized over and it was central to the narrative, not to mention among the most creative lines in the sensational ballad. Given, of course, that there were no survivors, it fictionized what one of the prominent crew members – the ship’s cook – might have said and done:

When suppertime came, the old cook came on deck sayin’

“Fellas, it’s too rough to feed ya”

At seven p.m., a main hatchway caved in, he said

“Fellas, it’s been good to know ya”

Pretty much “Mark Twain” stuff, except for the third line which would prove contentious, given the ongoing and compounded speculation as to the cause of the sinking.

It took less than a week to discover the wreckage of the Edmund Fitzgerald at a depth of 530 feet in Canadian waters. The 729-foot vessel had split in two. The investigation into the cause began immediately, but would stretch over many years involving several marine-associated bodies and site surveys. Despite various hypotheses, it was eventually determined that the cause of the sinking could not be conclusively determined.

The first theory by the U.S. Coast Guard in 1977 proved the most controversial. It concluded that the disaster was caused by ineffective hatch closures which allowed water to flood the cargo holds – inferring incompetence by the deckhands. This infuriated the crew’s families and affiliated unions. They believed the findings were tainted. And their concerns were somewhat vilified a year later when the National Transportation Safety Board concluded the Edmund Fitzgerald sank suddenly from cargo-hold flooding “due to the collapse of one or more of the hatch covers under the weight of giant boarding seas” and not flooding due to ineffective hatch closures.

As might be imagined, Lightfoot formed a close bond with the families of the dead sailors, including a ladies committee in Madison, Wisconsin, that included the wife and daughter of Captain Ernest M. McSorley. So he grew sympathetic to their views on the sinking, given, too, that this was his favourite song.

“The ‘Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald,’ that’s one I always treat with respect,” he told Broadview Magazine in 2013. “The part in the song about the hatch covers giving way as one of the possibilities (for the shipwreck), well that was the job of the deckhands. They were supposed to be the guys who were looking after the hatch covers.”

“I felt a cringe, I felt something in my soul, because they knew that wasn’t what happened and I had no business assuming what happened,” he added. “In concert, I change the line of the song to, ‘At 7 p.m. it grew dark, it was then he said, fellas, it’s been good to know you.’ No more hatch covers.”

It is thought to have been during a live performance in March 2010 that Lightfoot first changed the contentious stanza to:

When suppertime came, the old cook came on deck sayin’

“Fellas, it’s too rough to feed ya”

At 7 p.m. it grew dark, it was then he said

“Fellas, it’s been good to know ya”

And, as another appeasement, when one parishioner complained, he changed his description of the Mariners’ Church to sing:

In a rustic old hall in Detroit, they prayed

Instead of

In a musty old hall in Detroit they prayed

Despite the changes in live performances, Lightfoot decided not to change the original copyrighted lyrics. And, just to add more intrigue, he never changed the freighter’s destination. In song, it was Cleveland. In reality, it was near Detroit.

While much has been made of Lightfoot's live lyrical amendments in recent years, little has been said about an obvious omission in his telling of this sad story. And that relates to the now-famous last words by Master Captain McSorley.

During the final hours of the doomed voyage, the Edmund Fitzgerald was in constant radio contact with another freighter, Arthur M . Anderson, which was also battling the storm and could, at times, see the lights of Big Fitz traveling in the same direction. At 7.10 p.m., the first mate on the Anderson radioed McSorley, asking "How are you making out with your problem?" The Edmund Fitzgerald's skipper replied: "We are holding our own." It would be the last words ever recorded from McSorley.

Just imagine how Lightfoot could have cleverly intertwined those five words into his ballad? It must be assumed that he never did because when he wrote "The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald," the radio transcripts had not been released.

W

There are seven verses in the six-and-a-half-minute song. But there are no choruses. Instead Lightfoot repeatedly embraces the theme of the terrible weather common in the late autumn month of November on the Great Lakes.

And every man knew, as the captain did too

T’was the witch of November come stealing

The dawn came late, and the breakfast had to wait

When the gales of November come slashin’

He also endearingly laments throughout the ballad on how close the Edmund Fitzgerald actually got to a safe haven.

Does anyone know where the love of God goes

When the waves turn the minutes to hours

The searchers all say they’d have made Whitefish Bay

If they’d put fifteen more miles behind her

But it is the cruel November weather which provides Lightfoot with a fitting finale to this sad, but beautiful, saga.

The church bell chimed ‘til it rang twenty-nine times

For each man on the Edmund Fitzgerald

The legend lives on from the Chippewa on down

Of the big lake, they call Gitche Gumee

Superior, they said, never gives up her dead

When the gales of November come early

May the bell now continue to toll 30 times on each anniversary.

Paul Cutler

Editor Crossroads – Americana Music Appreciation

Comments